Let me tell you a story. Not the one they write in government white papers or oil company reports. I’m talking about the story written in the creeks, the story written in the blood, tears, and burnt-out remains of our communities. It’s the story of how a people keep standing up, and how a government keeps trying to knock them down, only to later offer a handshake stained with oil.

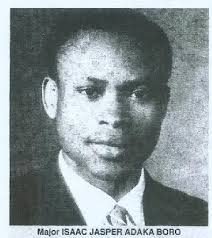

It didn’t start with pipelines or amnesty deals. It started with a dream. Isaac Boro dream in 1966 envisioned a Niger Delta Republic. It lasted only twelve days before the Nigerian Army moved in to crush it. Twelve days. That’s how long it took the Nigerian Army to crush it. Boro was sentenced to die. That was the first lesson: ask for freedom, meet the rope or the bullet. The government’s answer was always the same: Brute Force.

It didn’t start with pipelines or amnesty deals. It started with a dream. Isaac Boro dream in 1966 envisioned a Niger Delta Republic. It lasted only twelve days before the Nigerian Army moved in to crush it. Twelve days. That’s how long it took the Nigerian Army to crush it. Boro was sentenced to die. That was the first lesson: ask for freedom, meet the rope or the bullet. The government’s answer was always the same: Brute Force.

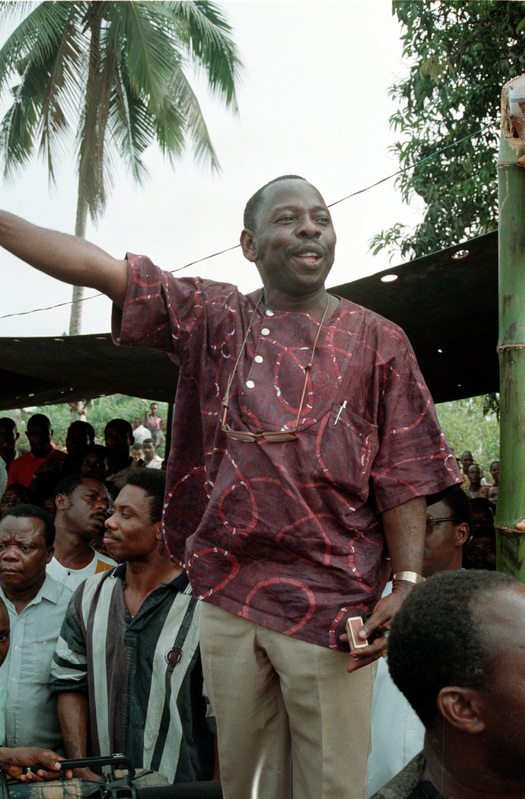

Then came the voice. Ken Saro-Wiwa. He didn’t carry a gun; he carried a truth so powerful it scared them more than any army.

He spoke of poisoned water, gas-filled air, and a land dying while a nation grew rich. The response from General Sani Abacha’s regime was a sham trial, a judicial farce that turned the law into a weapon. Despite passionate pleas for mercy from global figures like Pope John Paul II and Nelson Mandela, the sentence was executed: Saro-Wiwa was hanged in a Port Harcourt prison in 1995. It was a cold, calculated act of judicial murder. The world wept, yet the oil continued to flow uninterrupted. The lesson evolved: speak the truth, and the state will kill you legally.

When peaceful protest was met with hanging, what did they expect? The rage grew teeth. The era of MEND and the creek militants arrived. And the government’s boot came down harder than ever before.

I need you to feel this in your spirit, not just read it on a page. Let me take you back to November 1999, to the community of Odi in Bayelsa State. They weren’t chasing militants; they were punishing a town. When the gunfire finally ceased, Odi no longer resembled a living community; it had been transformed into a cemetery of smoldering rubble. Hundreds of our people; mothers, fathers, and children were eliminated. History remembers it as the Odi Massacre, an operation carried out under the orders of President Olusegun Obasanjo. The message was clear:

We will burn your home to the ground to keep our oil safe.

Ten years later, in May 2009, the violence returned, descending from sea and sky. Warships anchored off the coast, and helicopters hovered above as the full force of the state was unleashed upon Gbaramatu Kingdom. They bombed Oporoza, the traditional heart of the kingdom, and razed Okerenkoko to the ground. Families fled in terror, scrambling into the mangroves like hunted animals, forced to watch their ancestral homes, sacred sites, and history burn. This operation unfolded under the command of President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua. It was the same brutal playbook, executed once more: collective punishment. A scorched-earth vengeance inflicted upon a people whose only crime was living atop the pipelines that fueled the nation.

But here is where the story twists. After crushing Gbaramatu, the same government turned around and offered Amnesty. Lay down your guns, and we’ll pay you. It wasn’t justice; it was a business transaction. They swapped bullets for bank alerts. The most feared militant leaders became wealthy men on a government payroll. The fire of the struggle was doused with cash, not with the justice we demanded. Our demands was equivocal: resource control, clean water, a future.

Now, look at today. The latest chapter is the strangest. The same men they hunted are now paid billions in “Pipeline Surveillance Contracts.” Tompolo, once Public Enemy Number One, is now the government’s chief security contractor. It sounds like peace, but feel it in your spirit: is this victory, or is it a deeper, more clever conquest? They didn’t change the system; they just bought off the resistance and called it a solution.

So, what are the legal implications in all this? The law has been a spectator, and sometimes, a weapon. The sham trial of Ken Saro-Wiwa showed how courts can be used to sanctify murder when the state wants it. In 2005, a judge called the Odi massacre “illegal and genocidal.” The court ordered rebuilding and compensation which our government ignored. A judgment without enforcement is just paper. It means you can win in court and still lose in your burnt village.

This profound domestic failure has effectively exiled our pursuit of remedy, forcing our people to seek justice in foreign courts, like in Okpabi vs. Royal Dutch Company RDC, to seek justice for what our own nation refuses to give. That tells you everything about where we stand in Nigeria’s own legal imagination.

We are a traumatized people, generation after generation. We carry the memory of bombed communities and the quiet shame of a struggle that got turned into a contract. We have young men who see that the only way out of the creek is either through a gun or a government bribe, not through a school or a real job. We have a “peace” built on money, not on truth or restructuring.

The resistance has changed shape, from Boro’s idealism to Saro-Wiwa’s eloquence to the militia’s fury to today’s complex, paid-for calm. But the government’s answer has never truly changed at its core:

Force first, then buy off what you cannot break.

And in a bitter twist of history, while men like James Ibori and Governor Ainemesia are recorded as criminals today, a future, disillusioned generation might remember them differently, not necessarily as saints, but as pragmatists who in their own flawed way, understood and attempted a form of localised resource control, however corrupted. Come to think of it, if every governor who looted their state treasury were to go on holiday, Nigeria would be empty of former governors. That is the true measure of our national ailment.

Until the law means justice for the common Niger Deltan, not just contracts for the powerful, and until the government addresses the why and not just the who, this story isn’t over. The wound is still open. They just keep changing the bandage and calling it healed.

Who knows what the AI generation of Niger Deltans will bring forth? They will inherit our trauma, our memory, our defiance, and a new kind of clarity. They may look at the old cycles of blood spilt and then silence bought and reject both scripts. Their resistance may not march with guns or queue for contracts. It may speak through satellite imagery tracking oil spills in real time, blockchain ledgers tracing stolen crude, AI models mapping pollution’s toll on health, and digital campaigns that turn local grief into global reckonings.

They might weaponise data where we wielded machetes. They could sue not just in London, but in virtual courts of global opinion, forcing accountability through code and connectivity. Their battlefield may be the cloud, their evidence algorithmically unshakeable. They may return to a fiercer, older truth that a people stripped of dignity, watching their land die byte by byte, may one day rise with a final refusal to kneel.

As long as the land bleeds oil and the people bleed need, the struggle will transform. It may hide in lines of code, flow through fiber-optic cables, or rise again in the creeks. But it will not end. The wound remains open. They are still just changing the bandage.

Let us move with clarity, courage, and unwavering resolve now.

In solidarity,

Ogbevire Christian Ashaiku (AKA Daddy Kris)

PhD Research Fellow in Law & Human Rights

University of Hertfordshire, United Kingdom